An Empirical Review of Nvidia's Valuation: Separating Signal from Speculative Noise

In the contemporary financial discourse surrounding Nvidia, objectivity has become a scarce commodity. The conversation is dominated by high-volume emotional rhetoric, oscillating between unbridled euphoria and dire warnings of an imminent collapse. This polarization is fueled by two pervasive narratives: the specter of over a billion dollars in insider stock sales and the facile, yet powerful, analogy comparing Nvidia's ascent to Cisco's precipitous fall during the dot-com bubble. The effect is a market environment where analysis is often subordinated to anxiety.

This article will step back from the speculative frenzy. Its purpose is not to persuade through passion but to clarify through data. By conducting a dispassionate, evidence-based examination of the company’s financial structure, market dynamics, and the context of executive compensation, we can separate the statistical signal from the speculative noise and arrive at a more grounded understanding of Nvidia's current and future position.

The Flawed Precedent: A Quantitative Comparison to the Dot-Com Era

The most persistent bearish argument against Nvidia is the comparison to Cisco Systems circa 2000. On the surface, the parallel is tempting: a company providing the essential hardware for a technological revolution sees its stock price achieve escape velocity. However, a deeper, quantitative analysis reveals this analogy to be fundamentally flawed, ignoring the profound differences in market structure, profitability, and the nature of the underlying demand.

Cisco's business was built on selling physical routers and switches—the plumbing for the nascent internet. Its demand was primarily driven by a one-time, global infrastructure build-out. While immense, this was a finite project. Once the fiber was laid and the data centers were connected, the demand for its highest-margin products would inevitably plateau. The dot-com bubble was characterized by companies with high valuations but often negligible profits, buying equipment on speculative capital to chase theoretical future revenue.

Nvidia's market is structurally different. It sells computational engines—the drivers of artificial intelligence. This is not a one-time infrastructure project; it is the creation of a new, consumable resource: intelligence. The demand is not just to build a network, but to continuously power it with learning, analysis, and inference. Critically, Nvidia is not selling to speculative startups with no cash flow. Its largest customers are the most profitable companies in the world (Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud), which are themselves selling AI services to a global enterprise market. Furthermore, Nvidia’s financial profile bears little resemblance to a bubble-era firm. In its most recent fiscal year, the company reported a GAAP gross margin of 72.7%, translating massive revenue growth directly into staggering net income—a stark contrast to the 'growth at all costs' ethos of the late 1990s.

An Evidentiary Look at Insider Stock Sales

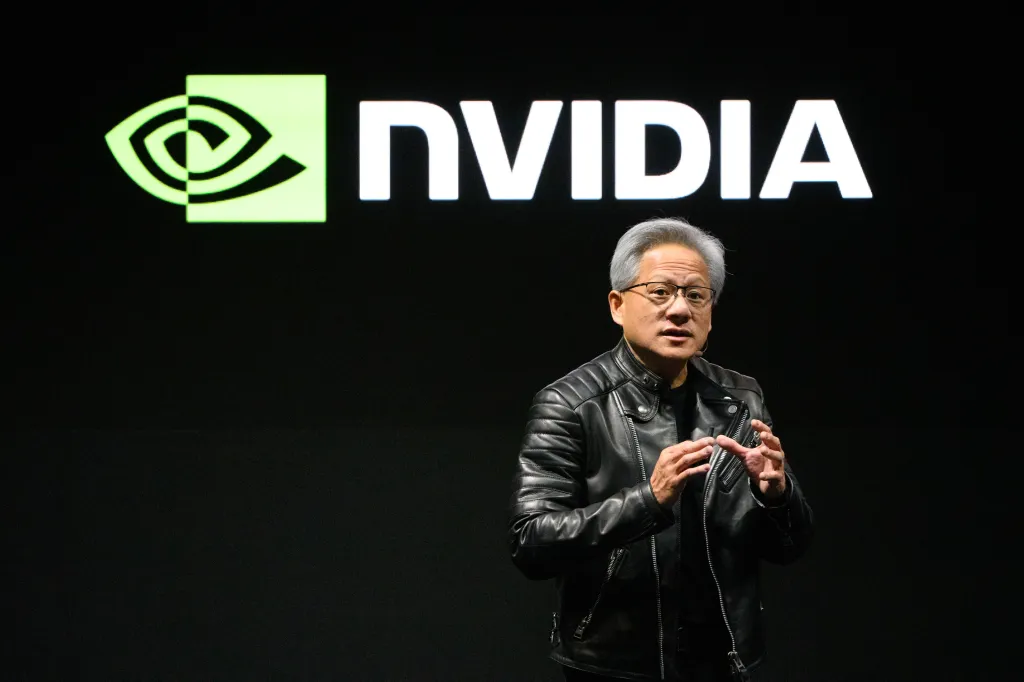

The narrative surrounding over $1 billion in stock sales by Nvidia executives, including CEO Jensen Huang, has been framed as a vote of no confidence. However, interpreting this data without its proper regulatory and financial context is misleading. A significant portion of these sales are executed under SEC Rule 10b5-1, which allows insiders to establish pre-arranged trading plans at a time when they are not in possession of material non-public information. This mechanism is designed precisely to prevent insider trading and allow for orderly, planned asset management.

For a founder and CEO like Jensen Huang, who has led the company for over three decades, his personal wealth is overwhelmingly concentrated in Nvidia stock. Standard principles of personal financial planning and risk management dictate diversification. It is not a signal of disbelief in the company's future; it is a rational act of wealth management. To put the sales in perspective, even after recent transactions, company insiders retain the vast majority of their holdings. For example, Jensen Huang’s reported sales often represent a low-single-digit percentage of his total ownership. This is not a rush for the exits; it is a measured, scheduled diversification strategy, a practice common among founders of every major technology company from Amazon to Meta during their high-growth phases.

Modeling Future Growth: The Sovereign AI and Enterprise Inference Catalysts

Fears of a slowdown in the AI hardware business misinterpret the maturation of the market. The initial demand surge was driven by building and training foundational Large Language Models (LLMs). The next, and analytically larger, phase of demand is twofold: enterprise inference and Sovereign AI.

First, the workload is shifting from training to inference—the real-world application of trained models. Industry estimates project that the computational demand for inference will ultimately dwarf that of training by a factor of 5x to 10x. Every time a user interacts with a generative AI service, an inference workload is created. As AI is integrated into enterprise software, consumer applications, and industrial processes, the demand for inference-optimized GPUs will create a massive, sustained revenue stream. Nvidia's product roadmap, with chips specifically designed for this purpose, is directly aligned with this next wave.

Second, the concept of 'Sovereign AI' represents an entirely new and durable customer category: nation-states. Countries across the globe, from the UAE and Saudi Arabia to France, Japan, and Canada, now view domestic AI computational capacity as a critical national resource, akin to energy independence or telecommunications infrastructure. This is not speculative venture capital; this is long-term, state-sponsored strategic investment in a foundational technology, creating a demand floor measured in the tens of billions of dollars annually.

In conclusion, a clinical examination of the available evidence leads to a clear set of findings:

- The Cisco dot-com analogy is a category error, failing to account for fundamental differences in profitability, market structure, and the consumable nature of AI computation versus the finite nature of network infrastructure.

- Insider stock sales, when viewed through the proper lens of SEC regulations and standard wealth management principles, do not indicate a lack of confidence but rather a rational and pre-planned diversification strategy.

- Forward-looking demand is not waning but evolving, supported by the immense structural catalysts of the enterprise-wide shift to inference and the emergence of Sovereign AI as a major new customer class.

Therefore, an analysis grounded in financial data and market structure suggests that Nvidia's market valuation is less a reflection of speculative mania and more a rational, if ambitious, assessment of the company’s central and foundational role in an ongoing technological revolution. The quantitative signals pointing to long-term, structural demand significantly outweigh the narrative noise generated by flawed historical comparisons and decontextualized financial disclosures.